Articles Home Page

Welcome to the Articles section of our website. It is worthwhile checking out each of the sections as we are constantly adding to the site. If there are any areas you would like covered or you have items for sale please contact us. pam@britishnotes.co.uk

Marshall Trial for a £5 note 1843, very ornate borders

A History of British Banknotes

The Bank of England, created by William Paterson, a Scottish merchant in 1694 to raise funds for the government of the day, partly to fund the Nine Years War against the French, which for five years had depleted the national exchequer. The Bank would raise money and lend it to the government. In return for risking its capital, it would be given certain privileges, the main one being the right to issue banknotes.

The idea proved popular. Fired with patriotism and the hope of seeing a healthy return on their investment, wealthy citizens subscribed £1,200,000 for stock in this new institution, taking the title 'the Governor and Company of the Bank of England'. The first Governor of the Bank, Sir John Houblon, a Huguenot, settled in London after fleeing religious persecution in France.

At first, the denomination of the note was handwritten, odd amounts predominately. Part printed notes appeared in 1695. In 1697 a watermark introduced by Rice Watkins showed a looped border and scroll on the left, with the words 'Bank of England' clearly visible for which an Act of Parliament prohibited anyone else from using.

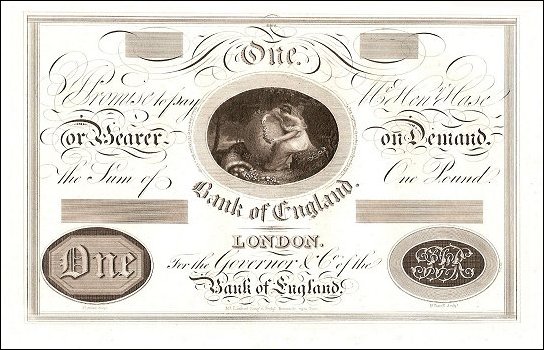

Originally the Bank would give depositors a receipt, handwritten, signed by one of the Bank’s many cashiers. These notes, like current issues bore the familiar words 'I PROMISE TO PAY', although these early notes would hold the name of the depositor and the amount deposited in the Bank they were on ordinary everyday paper from the local stationers, printed outside the Bank.

A bank officer represented the Bank at Portals, the paper makers at Laverstoke. As the paper was produced it was locked in iron chests and sent in Joseph Portal’s wagons to the Bank by road to Newbury and then via barge through the Kennet and down the Thames. At the Bank the cashiers took custody and at the start of every month, passed the reams he deemed necessary for the months printing.

Mr George Cole of Kirby Street held the contract to print the Bank’s notes. Each morning a cashier, with a Bank clerk, delivered the copper printing plates to Mr Cole, the cashier returned to work. The clerk would remain at the printers the whole day, looking after the Bank’s interests, mainly accounting for the bank note paper. The clerk returned to the bank in the evening, placing the copper printing plates back under lock and key. Nine shillings per ream was paid for the printing of the notes.

In 1791 Mr Cole brought his business within the walls of the Bank at their request, remaining independent. A printing office was established for control by the chief cashier. Mr Hulme supervised the control of the plates, paper and printing. When in 1795, Mr Cole died, the Committee of the Treasury appointed his brother, William Cole, together with Mr. Garnet Terry to be joint bank note engravers and printers to the Bank.

In 1797, when under pressure from the government of William Pitt the younger, the Bank temporarily suspended its practice of honouring banknotes with gold. The Governor, reluctant to see so much gold withdrawn from the Bank, as gold was needed for the war effort, decreed that the Bank should issue low denomination banknotes of £1 and £2 in lieu of gold coin. Thus, £1 and £2 notes were introduced.

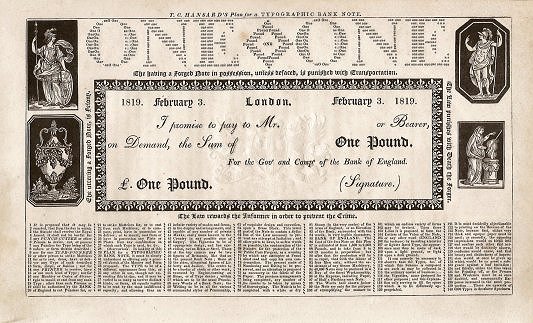

Hansard plate from the RSA book 1818

Plate from RSA book 1818

These new non-convertible £1 notes damaged the Bank’s standing and credibility for many years. The worry that not only the Bank’s notes were no longer backed by gold, but, also until this time, they had been restricted to issuing high denominations £5 / £10 / £15 / £20 / £25 / £30 / £40 / £50 / £60 / £70 / £80 / £90 / £100 / £200 / £300 / £400 / £500 / £700 / £1000. Branch notes for specific cities. Larger sums for official internal use only. The lowest value Bank of England note was for £5, the latter only being issued in 1793, more than an average working person earned for a year’s labour.

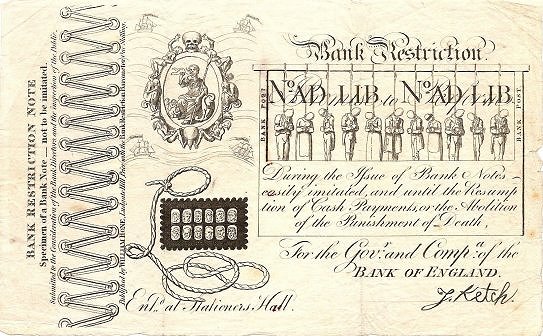

This measure, called the 'Restriction of Cash Payments' prompted a famous series of political and satirical attacks aimed at the Bank and Government. In the House of Commons the playwright, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, also a Member of Parliament, made a speech alluding to the Bank as an 'elderly lady in the City of great credit and long standing, who had unfortunately, fallen into bad company'.

This image of a compromised female virtue was taken up by the cartoonist James Gillray, who, under the title 'Political Ravishment of The Old Lady of Threadneedle Street in Danger' depicted the Bank as a gnarled spinster, clothed in pound notes, receiving unwanted attentions from a grasping Prime Minister.

The issued £1, £2 and £5 meant more of the general public had to come to terms with paper money. Banknotes were easy to counterfeit as many of their new owners were illiterate and not used to handling notes. Copper plate engraving was easily copied, yet it was the common mode in use at this time. Forgers easily exploited the uneducated Public.

The first man to hang for having forged bank notes was called Vaughan. He employed several engravers to each engrave a portion of a note. The plates were then joined and he took the guise of being a wealthy man. He was informed upon by one of his employees and subsequently hung on May 1st 1758.

The offence of 'uttering' a forged note could lead to deportation or hanging. Critics of the Bank knew that in many cases the 'utterer' was merely a pawn used by other people. In 1817 the Bank of England prosecuted one hundred and forty two people in connection with forgeries.

In 1818 two utterers had forged notes paid out and the notes kept by the Bank. The Bank prosecuted them for possession, but, they were acquitted (as they did not have the notes, the Bank did). Subsequently, the Bank decided to stamp notes such as these with FORGED returning them to the owners. This prompted, on the 22nd of January, a committee to be appointed to 'inquire as to the best mode of preventing forgery of bank notes'.

In 1819 George Cruikshank, a cartoonist of the time designed and printed 'The Bank Suspension Note', often referred to as the anti-hanging note, sold with a 'Bank Restriction Barometer' for 1s (shilling). The note depicted 'The Old Lady' eating babies – her public, surrounded by skulls and corpses, the sum block was a Hangman’s noose, the denomination made up of heads of those who were jailed. The signature was of Jack Ketch, the hangman of the day. Many women as well as men were hung at Newgate, for just handling a forged note, most people could not read.

Anti Hanging note signed by J Ketch, hangman of the day

Juries seemed to show a reluctance in enforcing the death penalty and the Act of 1820 had little affect on preventing the crime of forgery or of passing forged notes. The Bank, not indifferent to the poor 'wretches' in jail sometimes even paid monies to them for food and clothing whilst in prison, especially for those that had been awaiting transportation.

In 1820 an Act was passed for the better prevention of forging counterfeit bank notes. This act also allowed for the signature on the notes to be printed by machine instead of being laboriously signed individually for by hand.

The Bank also had one hundred and eight projects going on at this time with regard to its notes, but, all proposed alterations/designs had been successfully imitated by the Bank’s engraver, Mr William Bawtree.

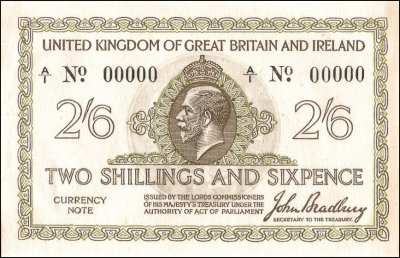

In 1914 just prior to the outbreak of the First World War, Lord Atterbury, Controller of H.M Stationery Office and Sir John Bradbury, the Secretary to the Treasury met at his house, overnight they produced a design for the emergency 10s and £1 note, however, no banknote paper existed except for that used for white notes and thus, for a speedy issue the simple cypher watermarked stamp paper was utilised. In order to make it as economical as possible, notes were also printed on the edges of the sheets, producing sideways watermark notes. The word POSTAGE or a part of it appearing on a percentage of the notes. Both Bradbury Wilkinson and Waterlow Layton and Brothers were contracted to print the notes and subsequently, De la Rue. The first issue red 10s and black £1, both uniface, were quickly put into circulation, picking up the nickname Bradbury’s.

A portion of the second issue 10s and £1 notes designed by George Eve, H.M’s designer of stamps, were overprinted for use in the Turkish Gallipoli campaign.

The third issue Treasury notes shows on the reverse a vignette of the Houses of Parliament by Bertram Mackennal, signed by Bradbury, subsequently by Norman Fenwick Fisher. They remained basically the same, though, on the final issue the title was changed to include Northern Ireland.

Due to a shortage of coinage, between 1917-1919 and again in 1941, various small denomination notes 'Fractionals' – 1s, 2s, 2s 6d (2/6) & 5s were planned, in some cases, stockpiled in large quantities, none were officially issued.

Treasury 2/6 Fractional Proof T22p

1925 saw the modern Britannia Design, Series 'A', brown for the 10s and Green for the £1. For this new issue, the first one hundred and twenty five pairs were individually packaged within a parchment envelope. The first twenty five given to Royalty, Heads of Government, etc., the remaining sets were offered for sale at the Head office of the Bank of England, not an immediate hit, some sets remained unsold.

The Britannia series 'A', in circulation until 1960 the only major changes being the issue of emergency war colours, mauve for the 10s and blue/pink for the £1. The white £5 remained in print until 20th September 1956, the longest running denomination in circulation 1695 to date.

B249 War time Specimen note 1940 to 1948, K O Peppiatt, chief cashier

Series 'B' was a short lived with only one design being accepted and printed, the Lion and Key £5, designed by Stephen Gooden RSA issued in 1957, (the type of £5 note stolen in the Great Train Robbery). The rejected designs include a note featuring Sir John Houblon, the first Governor of the Bank of England, who finally appeared on our current £50 some thirty six years later.

During chief cashier, Leslie Kenneth O’Brien’s tenure the Queen had ascended the throne, a new design was called for. Series 'C' known as the Portrait design, issued in denominations of 10s and £1. It was not until Jasper Quintus Hollom became the chief cashier that a new £5 appeared cutting short the life of the Lion and Key £5. The £10 re-introduced in 1962 after a gap of twenty one years.

Helmeted Britannia £5 Specimen of 1957, signed by L. K. O'Brien (Lion and Key note)

The Pictorial series 'D' £20 appeared in 1970. A fabulous design on the reverse, by Harry Eccleston, of William Shakespeare’s most famous scene from Romeo and Juliet. The £50 appeared soon after in 1981, the reverse an engraving of St. Paul’s Cathedral and Sir Christopher Wren. The first multi-coloured Intaglio note for the Bank of England

The Bank administers the bulk of the National Debt by selling gilt edged stocks for the Treasury and keeping a register of the two and a quarter million stockholders. As well as catering for the national Debt. The Bank looks after government assets, it manages the Treasury’s foreign currency reserves and its vaults hold much of the nations’s gold reserves. It manages the government’s major bank accounts and also holds accounts for the major banks, a number of large companies and other institutions.

The Bank contributes about a billion pounds a year to the Treasury by printing and issuing banknotes. The banknotes, since 2004 have been printed by De la Rue who took over the running of Debden Security Printers in Loughton, Essex, the printing arm of the Bank of England.

New innovations to our current notes include: holograms, fluorescent features, varnish coating, foil impression, ascending type size on the serial numbers, metallic thread with fine print etc., etc., The Bank still trying to keep one step ahead of the forgers.

Modern Specimen of 1998, Merlyn V Lowther signature